General Practitioners

The role of the general practitioner on the South Wales Coalfield was immortalized by A.J. Cronin’s novel, The Citadel, which was published in 1937. Cronin based the fictional Dr Andrew Manson on his own experiences of working as a doctor for a medical aid society in the Valleys. These societies were set up from the late nineteenth century. Workers arranged with their employers for an agreed sum to be deducted from their wages. In return, they gained access to medical attendance, nursing services and drugs, both for themselves and increasingly for their families as well. The Tredegar Medical Aid Society, for instance, was founded by miners and steelworkers in 1874, but 95 per cent of the town’s population were eligible for assistance by the 1920s. Where control of a society was won from employers, sharp conflict flared up with the British Medical Association and with local doctors who resented their accountability to a lay committee of workers. It is alleged that the medical aid societies influenced

Aneurin Bevan’s plan for the National Health Service that opened for business in 1948.

Link: Aneurin Bevan

|

|

|

Further

Reading

Cronin, A.J., The

Citadel (London: Victor Gollancz, 1937).

Digby, Anne, British

General Practice, 1850-1948 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Digby, Anne, Making

a Medical Living: Doctors and Patients in the English Market for Medicine,

1720-1911 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Honigsbaum, Frank, The

Division of British Medicine: A History of the Separation of General Practice

from Hospital Care, 1911-1968 (London: Kogan Page, 1979).

Loudon,

Irvine

, Medical care and the General

Practitioner, 1750-1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986).

Salwak, Dale, A.J.

Cronin (Boston: Twayne Books, 1985).

|

|

District Nurses

District nurses provided a nursing service for people who could not afford private home nursing. The nurses were provided by local voluntary district nursing associations, funded by private subscriptions. Contributions could be on an individual basis, by contributing small regular payments, or collectively through organisations and employers. Welfare organisations, trade unions, and co-operative societies, for example, made regular payments to local nursing associations.

In 1928, the National Birthday Trust was founded to promote maternal and infant welfare, and in 1934 it established a national survey to identify needs for district nursing. Local authorities had no powers to employ district nurses or support district nursing associations until the Public Health Act of 1936, although they could provide services for midwifery, school nursing, attending patients with infectious diseases, and rural health visiting. In addition to these services, the Poor Law authorities were able to provide assistance for the home attendance of patients on poor relief. Statutory provision for district nursing did not exist until it was included in the National Health Service of 1948. The administration of district nurses prior to 1948 was the responsibility of the county Medical Officer of Health and the nursing superintendent of the County Nursing Association, who was often a ‘Queen’s Nurse’.

A ‘Queen’s Nurse’ belonged to the Queen’s Nursing Institute, which was founded in 1887. The purpose of the Institute was to provide home nursing for the sick poor, and promote district nursing. Nurses were not employed directly, but were affiliated, trained, and inspected by the Institute. In 1897 ‘County Nursing Associations’ were introduced, which co-ordinated smaller rural associations and employed qualified midwives with an elementary training in home nursing. The Glamorgan County Nursing Association included Abercynon and Ynysboeth District, and Mid-Rhondda. The Institute did not represent all district nurses, however, as independent associations also existed. Nursing Associations in the South Wales Coalfield area included Aberdare and District, Abersychan and District, Ammanford District, Bedlinog, Cinderford District (Forest of Dean), Monmouth, Pontnewydd, Pontycymmer and District, and Porth.

Useful Links

UK Centre for the History of Nursing and Midwifery, http://www.ukchnm.org

Florence Nightingale Museum, http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk

Further

Reading

Baly, Monica, A

History of the Queen’s Institute: 100 Years 1887-1987 (London: Croom

Helm, 1987)

Baly, Monica, Nursing

and Social Change (London and New York: Routledge, 1995)

Robert Dingwall, Anne Marie Rafferty, and Charles

Webster, An Introduction to the Social

History of Nursing (London: Routledge, 1993)

Fox, Enid ‘District Nursing in

England

and

Wales

before the National Health Service: The Neglected Evidence’, Medical

History, 1994, 38: 303-321.

Stocks,

M., A Hundred Years of District Nursing

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1960)

|

|

Dentists

The Rhondda Medical Officer of Health (School Medical Officer) Reports of 1914 to 1947 provided details of dental defects found in school-children in the district, and treatments received. School children received dental examinations from a school dentist, for example, in 1923 Miss Poole of the Ynyshir Clinic fulfilled that role, and was assisted by dental nurses. Adults could obtain dental treatment if they paid for it themselves, or were covered by a welfare, workplace, or Co-operative Society scheme. Claims by miners for dental treatment, and dentures, were often received in relation to minor accidents which had taken place whilst working.

The first register of qualified dentists was set up as a result of the Dentists’ Act of 1921. No unqualified dentist could begin a practise after that date, however, many already practising were permitted to register. Dentistry was an unpopular profession at this time, with poor remuneration. The 1948 Spens Report showed that as well as dentistry being a low income profession, there were few working in rural areas, and large parts of the country were without dentists. Practices had been set up privately and dentists could charge their own fees. In middle-class districts, their social standing and income was reasonable. In working-class areas, however, their earnings were low, and their work consisted mostly of extractions. Only a few Approved Societies included dentistry in their benefits, and some only paid part of the costs. The only fully salaried dentists paid by the State were those who worked in school clinics, and infant welfare clinics, which were run by Local Authorities. These clinics ensured free dental treatment for expectant mothers until their children were 5 years old, and for infants and children until they left school at 14. A shortage of dentists often prevented adequate treatment, encouraging extractions in preference to fillings, even for children. When the NHS offered free dental treatment in 1948 there was an enormous demand. Most dentists who had worked privately registered with Local Executive Councils, but remained independent from the State.

Useful Links

British Dental Association Museum

http://www.bda-dentistry.org.uk/museum

History of Dentistry Research Group (University of Glasgow)

http://www.rcpsglasg.ac.uk/hdrg

|

|

Pharmacists

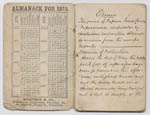

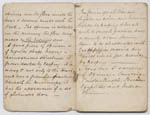

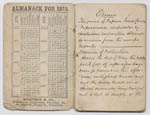

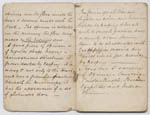

Opium notebook c1875

Opium notebook c1875

Edward Bevan was a pharmacist working in Swansea in the late nineteenth, and early twentieth-centuries. He was a member of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, which had been founded in 1841. The aims of the Society were to unite the profession into a single body, protect the members’ interests, and advance scientific knowledge. The qualifications of pharmaceutical chemists and apothecaries were first regulated by the 1852 Pharmacy Bill. Then, in 1865, the Chemists and Druggists (No. 2) Bill stated that from a set date, no person could trade under these titles until examined and registered. The 1868 Pharmacy Act recognised the chemist and druggist as custodian of named poisons such as arsenic, and also opium, which had previously been unregulated and freely available. Opium had been a medicinal constituent for centuries before this legislation, and continued to be available until the 1920 Dangerous Drugs Act prohibited its importation.

|

|

|

Further

Reading

Anderson, Stuart (ed.), Making

Medicines: A brief history of pharmacy and pharmaceuticals (Pharmaceutical

Press, 2005)

Kremers, Edward, and Urdang, George, History of Pharmacy: a guide and a survey (Philadelphia: Lippincott,

1951)

|

|