|

| You are here: Cwm > Themes > Love and hate > : Civil/Class Unrest | |

| |

|

Civil/Class Unrest |

|

|

|

|

|

Tonypandy 1910 | 1972/1974 Strike | 1984/1985 Strike The complex relationship between Colliery Owners and Workers highlights the human side of the quest for coal. The depth of feeling against the Owners by the Colliers has ranged from the early disputes over working conditions, pay, failure to take responsibility for accidents and the general treatment of colliers to the more recent, bitter strike over the widespread closure of much of the South Wales coalfield. Thus, the Coalfield has been the scene of much unrest as Colliers fought to have their voices heard. Riots, Lockouts, Stay-down protests, Hunger marches and Strikes have been the most evident form of protest and the following examples highlight the bitterness and strength of feeling felt at these times.

|

|

|

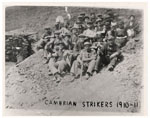

Tonypandy riots, 1910. The main reason for the miners’ disputes of 1910-11 was the change in the wage system that the owners were trying to introduce. Wages were linked to the amount of coal produced, but if the men were working with difficult coal, then the colliery company made up their wage with an allowance. The owners were however, worried about high wages, and so they began to refuse to pay allowances. In October 1910, there was a dispute at Cambrian Combine as some men refused to accept the new lower pay offer. 800 men were locked out and in November 1910, 12 000 miners went on strike. Violence broke out as the strikers stopped others miners going to work, and bitterness led to riots in Tonypandy. There was fighting between miners and the police, and most shops in Tonypandy had their windows broken. One miner died after a blow to the head thought to be from a police truncheon. When the rioting had ended, the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, sent troops into

the area to keep the peace. They stayed there for weeks and consequently, Winston Churchill was

unpopular in the area for many years. The miners returned to work in October 1911 when they were forced to return on the owners' terms and

conditions. |

|

|

1972/1974 strike. The Strike occurred because of disagreements between the miners and the Government over pay; throughout Britain's industry there was a widespread hostility to the Tories' offers of pay. In the 1971 NUM Annual Conference, it was decided to ask for a 43% pay rise, at a time when the Tories' were offering around 7-8%. In late 1971, the miners voted to take industrial action if their pay demands were not met. On the 5th January 1972, the National Executive Committee of the NUM rejected a small pay rise from the National Coal Board, who then 2 days later, withdrew all pay offers from the last 3 months. On the 9th January 1972, miners from all over Britain came out on strike. In South Wales, 135 pits were closed; 50 collieries and 85 private mines. At first the miners picketed at coal power stations, but then it was decided to target all power stations, and also steelworks, ports, coal depots and other major coal users. On the 9th February, a state of emergency was declared On the 19th February, after much negotiation, an agreement was reached between the National Executive Committee of the NUM and the Government. Picketing was called off, and on the 25th February, the miners accepted the offer in a ballot, returning to work on the 28th February. By 1973 the Arab-Israeli War was causing oil prices to soar, and throughout the country, relations between the industrial unions and the Government were hostile as the Tories were attempting to introduce pay freezes and restraints to help the economy. On the 9th February 1974, the miners again came out on strike. The Government refused to compromise on a 7% pay rise, and the situation lead to Edward Heath, the Prime Minister, to declare a state of emergency and introduce a three day working week. Following a general election on the 28th February the Conservatives were defeated and the new Labour Government and the miners reached a deal shortly afterwards thus ending the strike. Listen to the following video clip to hear a poem recalling personal experiences of the strike.

|

|

|

1984/85 strike By the late 1970s, a new industrial depression had started in South Wales. Pits started to be closed as did the factories that had brought employment to the valleys in the 1970s. This caused a rise in unemployment. People became increasingly concerned not only with the loss of jobs, but also the effect that the unemployment would have on the mining communities as a whole. These were nationwide problems. Margaret Thatcher was trying to diminish the power of the unions and in 1984 the National Coal Board declared that it wished to close 20 pits with the loss of 20 000 jobs, claiming that the deal made after the 1974 Miners’ Strike was no longer valid. On the 12th March 1984, Arthur Scargill, President of the NUM, called a national strike against the pit closures. Many miners were involved in picketing and protesting including miners from 28 pits in the South Wales Coalfield. The strike was however technically illegal as Arthur Scargill had not held a ballot of NUM members. The failure to call a ballot lead to the confiscation of NUM funds and enabled the Police to intervene to allow a handful of strike-breakers to go into work. This led to picket line violence, particularly in South Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire. There was much support for the strike in South Wales, although a collier was nearly killed when a concrete slab was dropped on his car near Merthyr. The miners wives played an enormous part in the strike. As well as appearing on the picket lines alongside the men, hundreds of women turned up at rallies and marched behind banners with slogans such as ‘Women Against Pit Closures’. They organised events to support the striking miners, from jumble sales to sponsored walks. They also organised food parcels and soup kitchens. The strike lasted for nearly a year, but on the 3rd March 1985,a special NUM conference was held and the miners bitterly conceded defeat. They returned to work two days later. In July 1985, there were only 31 pits left in South Wales. Listen to the following audio/video clips to hear peoples`various experiences during the strike.

|

|

|

Sources: |

|

Swansea University Special Collections

| ©University of Wales Swansea 2002 |